With the conclusion of the semester last week and the finishing of my research paper, my first class in PhD studies is at an end.

I loved every bit of it.

The opportunity to walk into a room, sit down and dig into a two and a half hour conversation on political philosophy with an accomplished Harvard scholar was worth the extra time, money and effort that was required.

In “Major Works of Political Philosophy,” we read what the professor considered to be the great works of Western political thought: Aristotle’s Politics, John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, and Hegel’s Philosophy of Right.

Aristotle and Locke I had read in previous courses during my undergraduate work, so reading them again was like deepening a relationship with an old friend. Indeed, I understood both men better having had the better part of eight years to observe politics, experience life, and engage with human nature outside the ivory tower of academia. It made for an enriching conversation. The surprise of the semester, however, was Hegel. Having read Kant’s Perpetual Peace, multiple works of Nietzsche, and Marx’s Communist Manifesto, I was relatively certain what I was going to get with Hegel.

Beware…. of running with scissors and other pointy objects…. and German philosophy.

When I told one of my friends what the reading list was for my class this semester there was the empathetic sigh and warning: “Good luck with Hegel, he’s a dense read.” Not comforting considering said friend has a PhD in philosophy and regularly lectures on German philosophers.

Another friend flatly stated, “I’ve made it a point to avoid German philosophy.”

There is a decided perspective on German philosophy: It is complex, morally ambiguous, and probably anti-Semitic.

Like Russian intellectuals, who are supposed to be depressed drunks due to long winters, vodka, and overlong novels; it seems Germans are to be considered obtuse stoics due to a war-torn history, mechanical prowess, and esoteric philosophy.

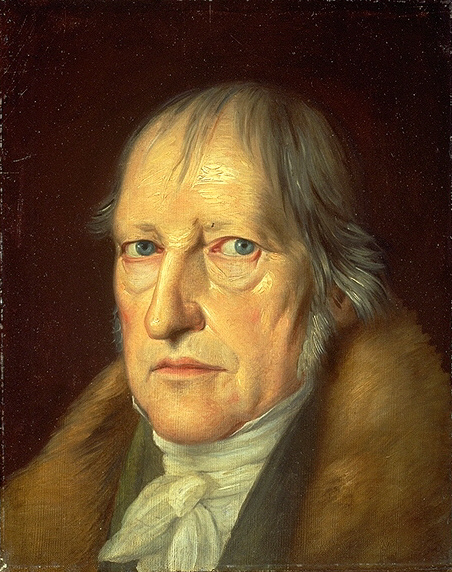

So, needless to say, I approached Hegel, the Godfather of German philosophy with a degree of trepidation, if not distrust.

After all, this was Mr. Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis, the dialectical foundation of Marx. I do not look with particular favor on this descendant of Hegelian thought, so I confess to a bias towards the forebear.

Hegelian Philosophy: Shock and Awe

I could not have been more mistaken about Hegel. Though he may well be considered the fountainhead of modern German philosophy given his pursuit of comprehensive knowledge (a desire to holistically understand the world), he does not bequeath the darker tones of thought to his academic descendants. Rather, one should think of those thinkers as having muddied the brighter waters of Hegelian thought.

In reading the Philosophy of Right, I was struck by Hegel’s confident tone, cogent reasoning, and his ability to interact with the major trains of political thought up to his own time. Three major components stood out to me.

First, Hegel rejects Kant’s distinction between morality and politics as a false dichotomy, and devastates the Kantian model for international government on the basis of nations being more like individual human beings – living entities who cannot, and will not, willingly divest themselves of personal identity and efficacy in deference to another individual entity, especially one made of of their own manufacture.

The freedom of the will, and it’s role in giving the individual the ability to act and identify as an individual ‘I’ is too hard wired into human nature.

Likewise, Hegel argues, nations similarly can only go so far in their cooperation with one another. International law can only ever be an association of individual national will, without a higher governing power. The many hurdles international organizations have had to deal with in the face of national prejudices and intransigence only serves to underscore this point.

Second, Hegel one ups Locke’s state of nature by looking at the state of the will and explaining fundamental equality of human beings through this lens. Because Locke looks at human equality through the lens of the State of Nature, human interaction, freedom, and equality are based in situational and contractual contexts. Though there may certainly be such an element at work in human society, Hegel goes further back than the State of Nature to actually consider what is ontologically true of humanity in terms of the will and the concept of identity (“I”). In doing so, Hegel is able to infuse Locke’s contractual world with such words as duty, love, family, and justice.

Hegel rediscovers the classical virtues in modern political thought in a way that Locke largely ignored.

Third, the Marx connection to Hegelian dialectic created a very negative connotation in my mind, but it is clear in Hegel that this dialectic of an object being challenged by an opposing negative, which helps form a new object is an exquisite literary devise to explain human development. Not unlike triptych art that creates a larger picture out of three distinct panels. Hegel uses this dialectical concept to not just make his arguments, but even to arrange the Philosophy of Right in its many chapters and subsections.

It provides beautiful symmetry to the work and actually helps one follow the argument more carefully. The fact that Marx only adopts this dialectical thinking in one aspect, and that of promoting the violent overthrow of modern society marks him out to be a philosophical charlatan.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx willfully dispenses with the finer points of Hegelian dialectics and asserts the violent interaction between bourgeoisie and proletariat that results in the destruction of the former and the rule of the latter. In this, Marx is using the dialectic models merely to push for the type of revolution that Hegel’s dialectic is actually trying to avoid via the mixing of thesis and antithesis to produce a synthesis. Marx would see the antithesis abolish the thesis, but that’s no synthesis…. that’s not even what it is by definition. If anything, reading Hegel has confirmed my dismissive attitude towards Marx. An influential poser, but a poser none the less.

In fact, Hegel is a new favorite of mine.

I am rather surprised to have come out on the other side of reading Hegel, and finding myself a fan. Maybe not yet a disciple, but certainly a fellow traveler (to a reappropriate a more Marxist term).

I have found that far from being the morally flexible, hardened pragmatist, or existentially conflicted German philosopher, Hegel offers one of the greatest defenses of human character and virtue. In fact, Hegel should be critical reading for American conservatives who may see him as too left of center.

Why conservatives should read Hegel.

Being of a more conservative bent, I found several of the major themes of Philosophy of Right to be relevant to the thought and concern of many conservatives. In recent years, and from my perspective, American conservatives have over-focused on the economic and legal arguments of Locke, the Founders, and other British thinkers. What is often missing in the thought and rhetoric that dominates conservative airwaves is a meaningful inquiry into the interaction of these social contracts with classical virtues. Hegel provides a framework for exploring this interaction, and does so using many of the words and concepts conservatives love.

Freedom

In Hegelian thought (not unlike Locke), freedom is not found in license, but in willingly choosing the good. Freedom is not even actualized without reflective thought, resulting in choice, and the willed pursuit of the good. Note the phrase “the good.”

Unlike his more morally relative philosophical descendants, Hegel believes in a definite, transcendent, knowable moral good. In this, one can see his strongest link to the classical pursuit of virtue one reads about in Aristotle, or Plato. The presence of this good, its pursuit, and its relevance to a stable, peaceful society is something that any conservative can appreciate.

What can be even more appreciated is where Hegel locates the individual’s pursuit of that good: The family.

Aristotle’s polis swallows the family and so has the power to regulate it excessively; Locke’s individual social contract sees the family as largely unnecessary to society; but Hegel sees love, marriage, and family as foundational.

In a marraige and the family unit, the tempering influence of the highest virtue – love- instructs the invidual will in duty and pursuit of the good. These two objects form the cornerstone of a virtuous citizen, who wisely exercises their freedom in, and for, the public sphere.

Duty and citizenship

Can you imagine a society where a child is instructed in what it means to love another, and to choose what is good for herself and for others? Duty would not be a bore, nor citizenship something to be cynical about. Hegel’s high view of governance, justice, and pride of working in the public sphere are quite in contrast to the political world we find ourselves in today.

I suggest working in the government to my students and I get rolling eyes and wrinkled noses. Propose that an indivudal has a civic responsibility to city, state and country to be aware of laws and elections and I get yawns. For Hegel, these are avenues for us to pursue the good and construct the type of civilizations we long to be remembered for.

Concepts such as duty and citizenship have fallen on hard times, and I cannot help but think that it is largely due to a loss of an ability to articulate “the good” in government, policy, and citizenship. This is moral high ground that neither liberal or conservative seem to truly fight for, though certainly lip service is paid to these high concepts.

Repudiating the revolution of Marx.

Like so many political philosophyers, Hegel was concerned about illustrating a just and secure society, and teaching his students it’s major tenets in the hope that such a society would be pursued and actualized.

Sadly, for Hegel, Marx’s bastardization of his dialectic obscured the finer points of Hegelian philosophy, promoting a view of violence as the only efficacy individuals had access to in the political world. Perhaps Marx saw Hegel as an idealist, which wouldn’t be hard to imagine given Marx’s penchant for sweeping overgeneralization, but to take only Marx’s word for it would be quite unfair.

Hegel’s thought should be considered a repudiation of political change through revolution because such violent overthrows rarely result in the kind of freedom and individual actualization Hegel seeks for the human will. And the loser is human society on the whole.

Hegel was an eye opening read for me in terms of understanding what political philosophy can be. Today, I fear political thought has grown overnarrow to the point where it is understood to merely be forming justification for ideologies when it should be given to understanding the great aims of human society and relationships, and creating the models by which those aims could be achieved.

Surely, such a pursuit is above ideology? When ideology is placed above philosophy, philosophy ceases to exist.

Hegel suggests a better way to think about politics:

Establish one’s presuppositions, justify them, then following them logically through to their actualization in the political realm. In such a way, Hegel should be more carefully read by liberals, and reconsidered by conservatives.

This was a wonderful read! Thank you for taking the time to write about this, it certainly has helped me see that I am among others who perceive a conservative nature to Hegel’s philosophy. I am studying history and philosophy at Georgia Tech, and I am a conservative — but one of a more classical, perhaps European breed — who was disillusioned by my radical libertarian beliefs upon reading Sir Roger Scruton. It was through Scruton that I was introduced to Hegel. I found a rich philosophy of homecoming that actually gives philosophical arguments to classical conservative values (such as family, community, social traditions, and so on) as opposed to the polemics (which are certainly important in their own right) of Edmund Burke. Here at GT, I am often accused of “dark-age” thinking because of my Hegelian outlook from those on the far left (which have not read any Hegel, let alone Marx or someone like Zizek to even know they claim to be Hegelian), and “statism” or even “socialism” by classical liberals who call themselves conservatives. Anyways, I plan to pursue graduate degrees in philosophy and focus on reviving the conservative Hegelian philosophy, reading this article was certainly an encouragement!

Thank you so much for the kind words, Micah. It’s tough being a conservative of any stripe in most academic settings these days, so I commend you for your earnest pursuit of knowledge and truth, which is what the conservative project is ultimately concerned with, especially in the realm of political philosophy. Current progressive and conservative ideologies in the US find it very hard indeed to comprehend Hegel. The left doesn’t understand that Marx is a poor interpretation/application of Hegel, and conservative (unfortunately) fail to understand the same thing. If they both understood Hegel in an elementary, but accurate, way, I think both sides would experiences a serious shift in how they feel about Hegel.