This last semester, I took a course in my political philosophy field on ethics and politics (yes, the two can go together). What I love about the field of political philosophy, at least the way my advisor teaches it, is the focus on in-depth understanding of ideas. We focus on only a couple authors at a time. This past semester was Aristotle (Nicomachean Ethics) and Kant (Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals and Perpetual Peace).

I’d read Perpetual Peace in the past, but reading now with one graduate degree under my belt and ten extra years of perspective, Kant’s classic work on what it would take for world peace took on new depth and meaning.

Read in the light of Aristotle, I got a fresh perspective on how to evaluate current attempts to make regional and global governance work.

I think most observers would agree that the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU) represent the most fully developed and realized attempts at achieving the kind of peace model that Kant presents. However, if one applies Aristotle’s definition of virtue as being a middle term between two vices (too much, or too little of the value), then a picture emerges wherein both the UN and the EU, best attempts though they are, fall far short of a virtuous attempt at “perpetual peace,” and instead represent the vices of too little and too much respectively.

What price that of peace?

Kant lays out basic criteria for a world capable of perpetual peace:

- Republican governments

- Non-intervention

- Free commerce

- No standing armies

Who wouldn’t want such a world of representative government, peace and commerce?

Especially in America, conservatives and liberals alike can find much to like in this kind of world: Freedom, equality, reduction of armies and conflicts, affirmation of rights, economic growth, and the list of benefits goes on.

Kant’s model for perpetual peace can be summed up in one phrase: Republican and cosmopolitan.

This is the virtue of global governance, the end that is to be strived for. However, by naming perpetual peace a virtue, we must ask the question: What are the vices?

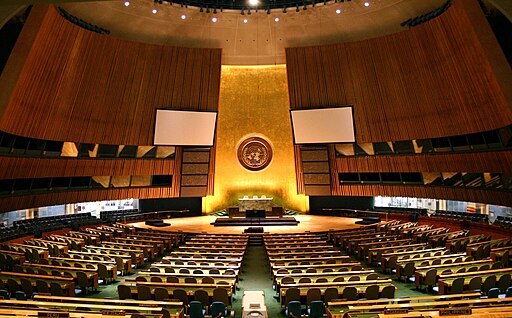

“Too little” vice: The UN

I call the UN the “too little” vice because it has too little republicanism and too little cosmopolitanism.

There are over 193 countries in the United Nations and the majority do not have representative forms of government. Of those countries that have representative governments, many are oligarchic and illiberal in nature. This means that the responsiveness to the population is limited, which creates distance between the rulers and the ruled, which necessitates oversized security apparatuses, which in turn leads to increased standing armies.

In order for more republican forms of government to work their magic at the global scale in the cause of peace, international organizations need to be more discriminating in their membership.

The UN, however, has become a “big tent” organization, welcoming all manner of governments. In the name of fairness and equality this has led to some really odd sharing of responsibilities as we’ve seen things like

- Iran leading a UN human rights panel

- Countries with strong illiberal governments routinely hold spots in the Security Council

- Aspirant illiberal governments like the Palestinian Authority are given recognition even as more republican governments like Israel get condemned.

One could argue that the UN at least started with the right ends in mind, but this would be a false assumption. By extending membership and a permanent Security Council seat to the Soviet Union at its establishment, the UN immediately distanced itself from the basic governance goal of Perpetual Peace: Republican government.

Kant’s basic argument is that republican government maintains a level of political accountability that places a check on international adventurism and conquest. Without such a check as electoral politics and representative government, a country may use an international organization as the proverbial bully pulpit in which to throw it’s legitimized weight around.

Arguably, one wonders if such regimes becomes a greater threat to world peace and lasts longer because of such legitimacy.

“Too much” vice: The EU

By contrast, at its formation the European Union was focused on the establishment of an international organization that had representative government as a core component of membership. In fact, lack of rights and freedoms, among other things, have been longstanding issues that have blocked accession to full membership for countries like Turkey.

EU member countries are called on to sign a charter recognizing civil liberties and rights, representative government, and cosmopolitan trade and travel. In keeping with the bigger challenge of Perpetual Peace, member countries have also been consistently cutting military spending over the last decade, greatly reducing the ability of European nations to singularly project power into other regions for interventionist purposes.

At first glance, the EU has checked off all the necessary boxes for perpetual peace to be achieved vis a vis Kant. It could be argued that the EU is a paragon of virtue in the world of international organizations.

However, the EU is guilty of being the “too much” vice in virtuous global governance.

The EU overstepped the Perpetual Peace criteria in two critical areas: Institutions and economics.

Institutionally, the EU has sought to be more than just a mere concert of nations. Its mission has been to essentially create a federal system, merging multiple independent states into one super state. To this end a European Parliament was formed, complete with Euro-centric political parties. A whole system of European political institutions was erected. The result has been deep and ongoing policy intervention in the internal affairs of other countries (something Kant is flatly against), which has created no small amount of distrust and frustration among member countries like Greece.

Greece is particularly interesting case study here. In the economic downturn of 2008 and the resulting sovereign debt crisis put the Eurozone and its currency (the euro) at risk of collapse. This was due in no small part to the economic failure of smaller EU-member economies like that of Greece.

In order to “bail out” member countries, keep their budgets solvent, and keep the euro afloat, strong countries like Germany created loan packages that required steep spending cuts in Greece, which led to riots, the collapse of governments, and the emergence of hardline parties on the left and right. The economic conditions created situations wherein one country was able to dictate policy terms to another country in a form of economic imperialism not seen on the continent in over a century.

Such actions created an instability it purported to solve and increased economic inequality within the union. However, more importantly, it weakened the legitimacy of the EU institutions and encouraged the rise of anti-EU parties, many of which have illiberal bents and have won elections (e.g. Hungary and Greece).

Too much governance created the problems that a system like Kant’s in Perpetual Peace seeks to solve.

Worthy beginnings, unworthy heirs

We’re thus left with two basic conclusions: A peaceful system of international cooperation and governance, a la Kant’s Perpetual Peace, is not possible, or it has been shown to work, but has fallen prey to illiberal forces.

What is clear, regardless of the conclusion drawn, is that the “successful” experiments in global governments have proven to be unworthy standard bearers for Kant’s noble goal of a world at peace.